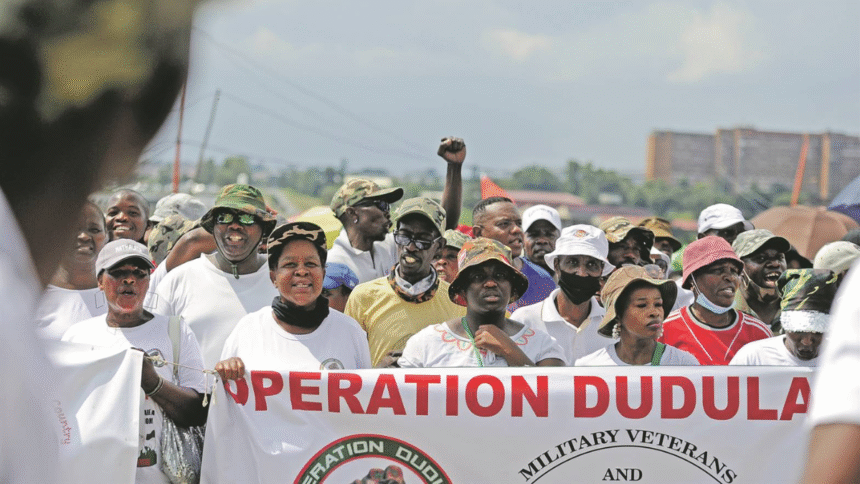

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa (Elevation News) — A South African court has delivered a landmark ruling against the anti-migrant group Operation Dudula, ordering it to stop blocking foreign nationals from accessing public hospitals, clinics, and schools. The judgment, hailed as a significant victory for human rights, comes after months of tension and intimidation targeting migrants across Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces.

Operation Dudula activists had been picketing outside health facilities, demanding to see identity cards and preventing non-South Africans from receiving medical treatment. The campaign later expanded to schools, where activists sought to stop the enrollment of undocumented children.

But on Tuesday, Judge Leicester Adams of the Johannesburg High Court ruled that the group’s actions were unlawful and unconstitutional, instructing them to cease “intimidating, harassing, or interfering with access” to public institutions.

He further prohibited the group from making hate speech, carrying out forced evictions of foreign nationals, or instigating others to do so. The court also placed restrictions on law enforcement, ruling that police may not conduct “warrantless searches” or demand identity documents unless they have “reasonable suspicion” that someone is in the country unlawfully.

Kopanang Africa brought the case forward against Xenophobia (KAAX) and other civil society groups, who accused Operation Dudula of inciting hate and undermining constitutional protections.

“This judgment provides critical protection for those targeted by xenophobic attacks,” said KAAX in a statement following the ruling. “In a country founded on the rejection of apartheid, we cannot allow ourselves to be subjected to the xenophobic hate promoted by Operation Dudula.”

KAAX said it would work with community organisations to monitor schools and hospitals to ensure compliance with the court order. It also vowed to hold police accountable should they fail to enforce it.

“If the police fail in their duty to uphold this judgment, we will report their inaction to formal oversight bodies,” the group told the BBC.

South African police have faced heavy criticism for allegedly failing to act against Operation Dudula. Rights organisations accused them of standing by as activists blocked hospital entrances and intimidated health workers.

Several Dudula members were arrested in August after disrupting healthcare services, though they were later released with a warning.

The group says it is “disappointed” by the ruling and intends to appeal, claiming it was only acting to prioritise South Africans in an overburdened healthcare system.

The term “Dudula”, which means “to push back” or “to drive out” in Zulu, reflects the group’s self-declared mission to remove undocumented migrants from public spaces and workplaces.

According to official figures, South Africa hosts around 2.4 million migrants, accounting for nearly 4% of its population. Most come from neighbouring countries such as Lesotho, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique, which have long supplied migrant labour to South Africa’s mines, farms, and factories.

But as unemployment and poverty rise, anti-migrant sentiment has become a powerful political weapon. Activists blame foreign nationals for taking jobs and straining public services, while analysts say politicians have failed to address the structural inequalities that fuel resentment.

Xenophobia has been a recurring issue in South Africa’s post-apartheid history. Periodic outbreaks of violence, often sparked by economic hardship, have left hundreds dead and thousands displaced.

Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi welcomed the court’s decision, saying it was “to be expected” as it aligned with the government’s stance that no one should be denied healthcare based on nationality or immigration status.

“Whatever concerns Operation Dudula has, some of which might be legitimate, they are using the wrong method,” Dr Motsoaledi told local broadcaster 702.

He acknowledged that South Africa’s public healthcare system is overstretched but noted that turning away undocumented people was impractical, as 11% of South Africans lack national identity cards.

The minister also called on neighbouring countries to help reduce migration pressure, arguing that South Africa bears the brunt of regional inequality.

“It is South Africa that is suffering, not them,” he said. “In fact, many of them are relieved.”

Human rights defenders say the ruling marks an important step in reaffirming South Africa’s constitutional values of equality and dignity. Yet many warn that the roots of xenophobia run deep, driven by economic desperation, political opportunism, and social division.

For now, the court’s decision sends a clear message: no one should be denied access to essential services because of where they were born.

Whether this judgment can help heal fractures between citizens and migrants, or becomes another flashpoint in South Africa’s ongoing migration crisis, remains to be seen.